My Take On Resilience

Before I continue down the winding road of my journey through Hazelden and then becoming a house husband, I want to share my thoughts on the patterns of thinking and behaviors that have made me so resilient, at least in the eyes of people like my friend Ann Masten (a world authority on resilience), who know about such things.

But first, a comment on writing. The process of writing this newsletter has been transformative for my thinking and understanding of so many things with greater depth. On its own, the brain and all its thoughts are like the mixing bowl of a stand mixer with all of the ingredients swirling around in a jumble nonstop.

Writing is like making a meal (hopefully one that others will enjoy!). All the ingredients that have been added to the bowl (my brain) from my experiences and relentless reading being tossed around and mixed up by the whisk attachment are emptied out onto the page to be cooked up for you all.

One of the other great things about writing is that you actually learn and gain insights as you write (for more on this topic, I highly recommend Writing to Learn by William Zinsser).

So why am I telling (writing) you all this?

Because, as I have been writing and sharing these stories with you, I have come to see a pattern in how I respond to adversity that has been almost (actually, completely) innate. And the more I have written, read, and thought about all this, the clearer the pattern has become. It's a system that seemed to be built into me, then reinforced or brought to the light of day by the challenges that life had in store for me.

So, the system for being resilient I've outlined below is my take on the system of resilience I've spontaneously deployed in my own life, using my experience at Hazelden as an example to illustrate the elements in action. Note that I have labeled them steps. The word steps suggests a sequence, or a recipe. For more minor setbacks or time-limited ones, the recipe and steps as outlined work great. But when the shit really hits the fan (like getting sent up to Hazelden), the steps are the ingredients that one pulls out of the mental cupboard depending on the moment and immediate situation. Sometimes you just need to detach. Sometimes you just need to reboot your commitment to what you will not accept. It depends.

And now (drum roll please!) I introduce the battle-tested Michael Maddaus Resilience System, which has served me so well with problems in my life of all shapes and sizes, from small to overwhelming. It is only when I didn't follow them that I ended up in trouble.

Note: the system is all a mental game, upstairs, in our heads.

Step 1: Detach

From the ego, emotions, and old perspectives that keep you locked in the past and stuck with things like anger, the need to be right, resentment, identity, and other psychological pitfalls that can keep you stuck in the pit of despair.

The challenge is that you can feel as if you are being roasted on an open pit when all the anger, the resentments, the fear, the ego, the need to be right - all the programming of the past - is fanning the flames roasting your brain.

In my case, entering Hazelden after being told to leave work immediately and just deal with it, hatred of myself for the mess, overwhelming worry about my family, and the fact that my whole sense of who I was (my singular identity as a surgeon) was now up for grabs.

Plus, I was so locked into my surgeon's perspective on how the world operates that I was quite blind to other perspectives. My frozen tundra-like perspective was highlighted in the 360 I had done several years before the addiction:

"Dr Maddaus is simultaneously harsh and largely unyielding unless one is in near-total agreement with him. Nevertheless, his overwhelming popularity is a testament to the potency of his personal strengths. Although his strong sense of self makes him courageous in many regards, I think his unshakable self-confidence (and sense of being 'right') often closes him off to other perspectives that are gentler or quieter than his own. In some ways, he seems almost ruthless in his pursuit to make us strong, leaving a trail of somewhat crushed personalities, which I think he believes is good for us."

No wonder I was voted (no joke) "least likely to succeed" by my fellow inmates early on.

There is a video game called Katamari Damacy which, in full disclosure, I have not played. In it, there is a little Prince (a child, like all of us at one time, and that is still somewhere in you if you look) whose father has destroyed parts of the universe. The little Prince has a magical, highly adhesive ball called a Katamari, which, when rolling around, sticks to any object it encounters. As it keeps rolling around collecting all the objects in its path, the Katamari ball gets bigger and bigger, and as it grows, it becomes more and more powerful.

We (our brains) are like Katamari Balls. We roll through life collecting ideas, beliefs, perspectives, all of it, and over time the power of all those things collected by your Katamari Ball brain gets more and more powerful. By the time you are 57 like I was when I entered Hazelden, when I received the award for least likely to succeed, the ball is a force to be reckoned with, a juggernaut. This is the force I had to deal with during my time in Hazelden and for a couple of years afterward.

The goal here is to try to do what the the spiritual teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti tells us to do as a matter of practice (paraphrased and with a few of my own words added by me): to have your mind stand completely free of past knowledge, biases, beliefs, identities - all of it - and meet the unknown without seeking refuge and comfort in the familiar.

In other words, to the best of your ability, detach to the mindset of being a child again, to having a beginner's mind, where you may see reality and yourself with the open, receptive curiosity of a child.

Step 2: Think Problem? Good!

This is a mindset shift away from any tendency to be a victim. I hate being a victim, and being a victim is a mindset issue. Sure, we are absolutely victims of events out of our control, but we don't have to be victims psychologically. It's poison to the soul. Jocko Willink's Problem? Good! shifts the mental gears away from reverse and into first gear, moving forward, so you can start to adapt, learn, grow, and change, despite the circumstances at hand. It is about having faith in yourself.

Let me be clear. None of this stuff is easy when you seem to be sinking into the quicksand of a major event, when all of the emotions and fear dominate your mental landscape. But do it anyway, or you will stay in reverse gear.

It is critical to know that the victim's voice and negative thoughts will keep bubbling up unbidden in your neurologic cauldron, and that's normal. Don't criticize yourself for them. They are natural and expected. But you can challenge the thoughts. In my case, when I was in Hazelden, the thought "now I'm nothing but a washed-up drug addict" tormented me. But I kept trying to remind myself (cognitive reappraisal - some days were way better than others!) that I was still a husband, a father, and a physician, and that I am a struggling human being like everyone else, and not "just an addict."

Not so easy when you have been exiled from work and everyone in your personal life is appropriately leery, angry, and exhausted.

Whenever you find yourself getting drawn in by the gravitational pull of the black hole of black-and-white negative thinking, remind yourself of the fact that it is normal to feel the pull of the situation, and light up the afterburners of cognitive reappraisal (evaluating an emotionally charged situation from a different perspective than what comes automatically to mind) to break free so you can keep yourself from getting crushed and small.

Step 3: Accept, Embrace, and Confront Reality.

When reality sucks, the urge to avoid reality can be overwhelming, to say the least. One of the more common experiences of my desire to avoid reality in a bad situation was after a significant operative complication. The pain of telling the patient's loved ones could be dreadful, especially with a major complication. It is one thing to tell them about the complication. That's hard enough. But to go by and see the family day after day while the patient is sick as hell, especially when the complication was an avoidable technical error on my part - it was miserable - and the gravitational pull to avoid the situation was powerful.

But avoiding the family only leads to anger, frustration, and a sense of abandonment, and my avoiding reality only made things worse for me over time. Thus, not only would I need to accept the situation in my bones - I had a preventable technical error that I needed to admit to myself, the family, and to my colleagues at complications conference, but I needed to fully embrace the process of being there for the family and the patient, regardless of how I may feel inside. This meant that when I went on rounds, I confronted reality every day by walking into the room with an open heart, compassion, and steady nerves, prepared for the understandable frustration and challenges the family was facing.

You can run from reality, but you can't hide.

With my Hazelden situation, I accepted (finally) that I was addicted to narcotics, it was a complete disaster that affected everyone in my orbit, it led me to this institution, and now, if I want to rebuild my life, I can either begrudgingly go along with the process and just get through it with the goblins of mental resistance holding me back like a dog in a harness, or I can accept my new reality without resistance or attachment to any outcome, and from that mental platform, get on the train and embrace the trip to mental and emotional healing so I could get back home to take care of and help heal my family. I confronted my new reality by going to every lecture and every group session, and doing as I was told by the program, no matter how I felt.

Step 4: Decide What You Will Not Accept.

I love paradoxes. I say accept reality, and now I am telling you not to accept something.

I came across a YouTube video by Jocko Willink entitled Jocko Does Not Accept This. You Shouldn't Either, it hit me like a ton of bricks. The notion of not accepting something, just the opposite from the Acceptance step above, perfectly fits what was going on in my neurologic engine in times of serious challenge.

In the video Jocko recounts the story of UFC fighter Jeremy Stephens who, with only some wrestling experience in high school, was getting ready to fight a black belt in Jiu Jitsu. He came to Jocko to help him get ready, and of course there was no time to teach him enough Jiu Jitsu to get him up to speed. So they decided that he could not accept being taken to the ground, because if he ended up on the ground he would lose the fight. It worked. He won the fight because he would not accept being taken to the ground. So in times of challenge, decide what you will not accept!

In the case of an operative complication, I could not accept the fallout from the resentment and anger that could ensue or get worse if I avoided the family. Not only would the guilt torment my brain forever if I avoided them, but I could not accept having a patient or family leave my care and my thoracic surgical service bitter and resentful. My reputation mattered to me, and it mattered to my referring physicians, and it mattered to the growth of my practice. I could not accept this.

In the case of Hazelden, I could not accept being a drug addict, and even though I was not a fanboy of the 12-step program, I knew I could not accept ever being reduced to the hellish state of demoralization and loss of my soul to another addiction. So I determined to do everything in my power to not accept being taken down to the ground again by a drug or any other addiction.

Step 5: Reframe your perspective on the problem.

The first step, Problem? Good! jump-starts the process of moving from being a victim to having an agency mindset, but the ultimate mental motivational fuel to move forward comes from reframing the situation as not only a setback but also an opportunity.

It is the fork in the road we all face, some more than others. Go left and stay on the gravel dirt road with all of its potholes, and life will continue to be unnecessarily rough. Go right to a new but unclear destination, and the road will eventually turn to a paved highway with all sorts of new places to see and experience.

This is where you get to decide how you will think about the problem in a way that gives you the energy, purpose, and motivation to take a right onto the road of your choosing.

Notice I said, "How will you think about the problem?" This is not necessarily about having a grand vision for some pie-in-the-sky future of living perfection borne of hardship. It is about believing, in your bones, that there is an opportunity for growth, learning, and evolution in the process if handled well.

It is really about faith. Faith in yourself, and faith in the universe of cause and effect. Recall that I wrote this note to my son Sam early in my time at Hazelden:

"Sammy, all I can offer you is to have faith. Faith in me, faith in the belief that I will do everything in my power to fix this situation, and faith that I will bring our family back to order, and faith that maybe we will all be even better off than before."

But there is another thing to have faith in: Fortuitous Concatenations. A fortuity is a chance occurrence or event, and a concatenation is a series of things that depend on each other as if linked together. Thus, a Fortuitous Concatenation is a series of fortuities that depend on each other, as if linked together.

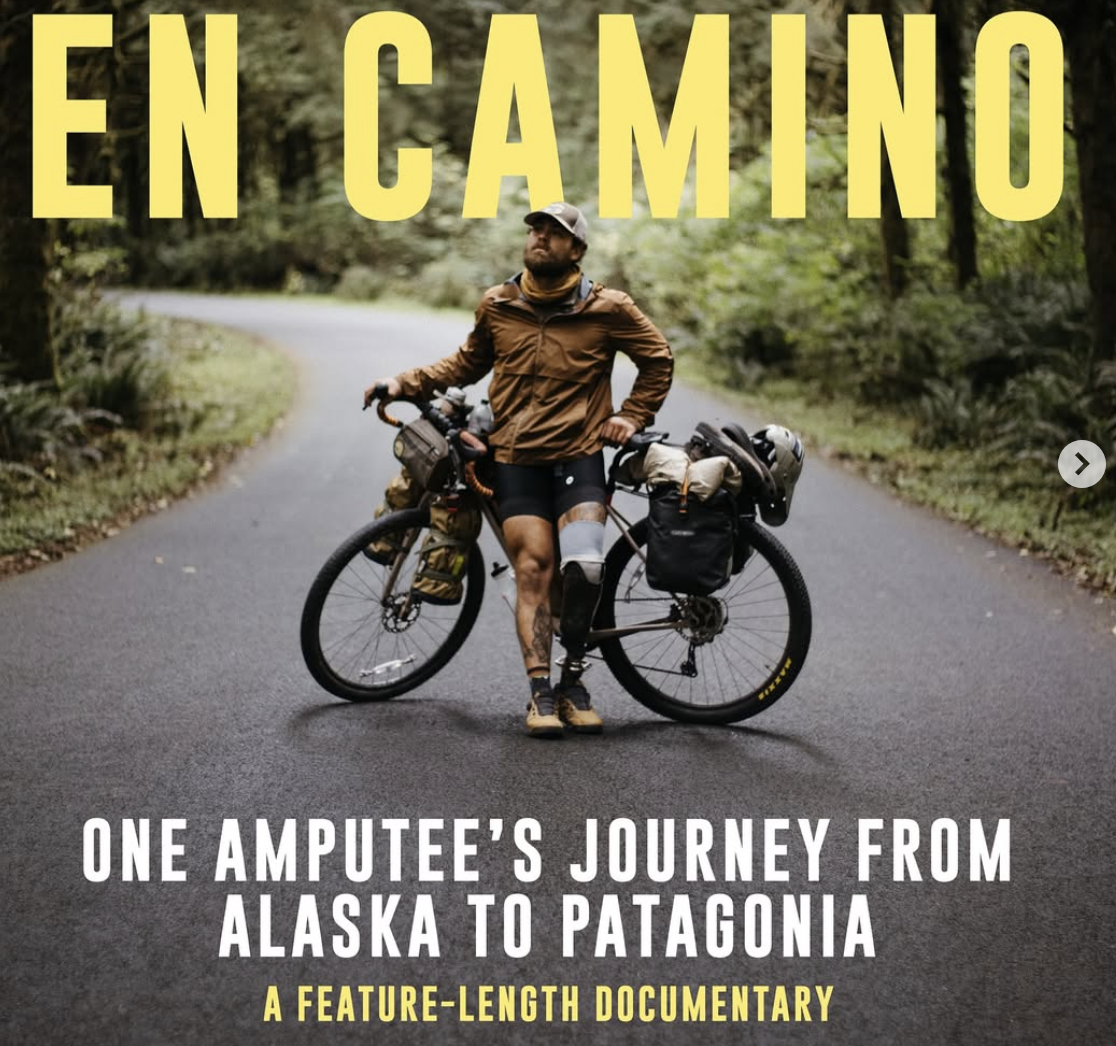

A recent and perfect example from my son Sam's life. He has just completed a 21-month bicycle trip from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, to Ushuaia, at the southernmost tip of South America in Argentina. He just set out to do the trip. He had no plans other than just doing the ride and capturing some video and pictures along the way to document his experience.

Our daughter Anne was a student at Loyola Marymount in Los Angeles, a school with a great undergrad film program. She just happened to see an Instagram post from a film student she didn't know named Dylan Marzke. She reached out to him about Sam's trip, and two things came of it. First, they are making a full-fledged documentary about his whole trip, having filmed him at multiple places on his journey, and they just left Minneapolis after interviewing me. The documentary has turned into much more than a story about his incredible feat. It is a story of his evolution from childhood to the amputation, and it's about his struggles to overcome his amputation to be able to pull it all off.

No matter where you think Fortuitous Concatenations come from - God, destiny, the universe - this stuff is for real. But, you must pay attention to the call of the fortuity, get clear if your intention for following it is the right fit, avoid the natural resistance that seems to crop up, and then you have to act!

Step 6: Act.

Start taking small action steps forward down the path to the new but unclear destination driven by the world of Fortuitous Concatenations, so you can avoid the thing you will not accept, and so you can enter a new universe of possibilities.

The Neutral Zone.

The last piece of the resilience system that is crucial to be aware of in the midst of major setbacks is the Neutral Zone and self-compassion. In military terms, a Neutral Zone is a space or a buffer zone between territories of different powers.

William Bridges (now deceased), an expert on human transitions in the corporate world (think layoffs, reassignments, downsizing, etc), used the term Neutral Zone to describe the window of time after a major life setback when there is emotional and mental turmoil. One day, your brain is used to the world one way, and suddenly it's faced with upheaval and change. It takes time for the neurons to adjust and adapt. They are slow to move and change their wiring circuits.

Bridges wrote a beautiful and very personal book about his own transitions called The Way of Transition: Embracing Life's Most Difficult Moments where he highlights how important it is to be muscularly patient and self-compassionate with ourselves until the turmoil starts to clear. The length of the turmoil will vary from person to person (genetics, upbringing, etc), and it will vary depending on the severity of the event (getting laid off, death of a loved one).

Once the neurological dust settles, one can think more clearly and make better decisions about the future.

There you have it, my take on my personal journey with resilience. If you are so inclined, please send me any feedback on your thoughts or ideas, or a thumbs up or down.

Thanks for reading🤗