Story # 3: Audrey, the TCOIC boss.

Apparently, St. Croix forestry camp and the hell I endured were not a sufficient deterrent. Not long after gaining my freedom, I found myself in the middle of the night intoxicated and on the roof of Len's grocery store smashing the small skylight with my foot and then lowering myself into the store. After crashing down on the Cheeto and Frito Lay stand and finding myself sprawled out on the floor surrounded by my favorite snacks (seriously, especially Cheetos) I looked up to see red lights flashing against the windows along with two cops.

My 25th arrest. As they say, I was a slow learner.

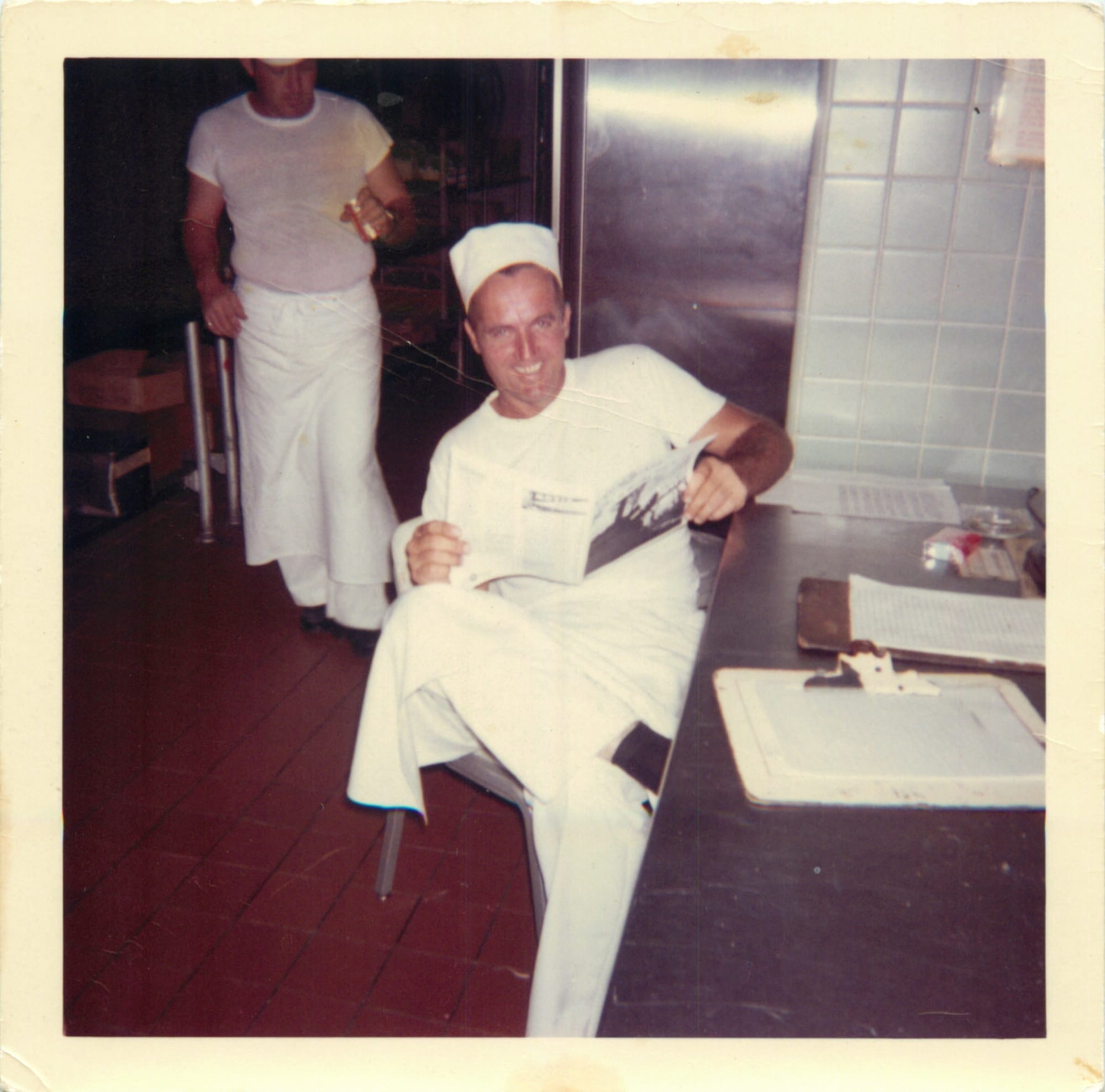

So, to avoid being tried as an adult and going to prison, I dropped out of high school and, per the sage recommendation of my "step-father" Ralph, whose life's work was as a cook in the Navy for 20 years, joined the Navy.

I ended up on an aircraft carrier with 50 other high-school dropouts just like me which meant I was a paint-chipper, latrine cleaner, and general fuck up and trouble maker.

One night, while we were out at sea, I was manning the watch alone at the back of the carrier, sitting in a rusty wire chair smoking a joint (this is during Viet Nam and drugs of all kinds were readily available on ship) when, while taking in the cosmic feeling of the vastness of the ocean and stars above me, it hit me upside the head like a sledgehammer that when I get out of the Navy I only three options: get a shitty job like painting for the rest of my life, more trouble and prision, or get my GED and go to school.

So, after discharge, I moved into an apartment with Chuck, one of my teenage friends who was not a troublemaker, but a cautious follower. I would steal the cars while he waited a block away for me to pick him up. Chuck was only arrested two times and never sent up to reform school, compared to my record breaking 25.

Money was the paramount issue on my plate even though I had the GI Bill for school. No mom and dad to help or home to land in till I get my shit together. So I had an afflatus (at least it seemed so at the time - but more like a shitty idea!): learn a trade like welding so I can work, save money, live, get my GED, and then go to school.

I lived in south Minneapolis, and I have no memory of how I found the place, but on the other side of the city, in north Minneapolis, in a predominantly black community, there was a trade school called TCOIC (Twin Cities Opportunities Industrialization Center). Put bluntly, at the time, it was a dump of a place that had a couple of welding rooms with an old, cantankerous, impatient man who seemed to be irritated just by the sight of me. I don't blame him.

There is a scene in the Woody Allen movie Everything You Want to Know About Sex (the vignette starts at 1:50:42) where a white man is having intercourse with a woman in a car. There is a scene that takes place inside the man's body showing what is going on during the car mayhem that includes a long white tunnel with white actors dressed in white sperm outfits with white caps and tails, all holding onto overhead subway-like handles, one of whom is Woody Allen. Woody is of course, extremely anxious about his fate when launched into the abyss, and he is mumbling away to the other sperms around him about the stories he has heard of past sperms dying upon hitting a rubber wall. Then the camera pans down the line of white sperm until we encounter one lone black sperm (a black guy in a white sperm outfit) who is staring down in a trance of desperate resignation while mumbling "what am I doing here?, what am I doing here?" over and over.

That's how I felt every day at the TCOIC.

It didn't take long before I knew that donning a black helmet while brandishing a fire stick and inhaling fumes was not for me. But I needed help figuring out the GED thing. The year is 1974, and there is NO internet. And I have zero skills for for navigating and living in the real world. My life then was all about on-the-job training.

Audrey, the young black woman who (so it seemed to me) was in charge of the place, came to the rescue. I was a clueless, uneducated, skill-less, young, barely ex-delinquent drop-out who, with my homemade tattoos, was judged by many as being a worthless loser and not worth the time of day. That was the clear message I got day in and day out from the kids from Kenwood (the tony neighborhood where many of the kids I was in school with lived) and from my teachers during my years in junior high and high school.

Then one day, after practicing welding one piece of metal to another, I lifted my big black helmet face up, coughed from the fumes, and said Sayonara to welding. On my way to the door, I started fussing about the GED issue, and I passed by the open door to Audrey's office. She was sitting at her grey metal industrial-like desk in her tiny office, working.

Without hesitation, I walked in and asked her if she knew anything about how to get a GED. After taking a long look to size me up a bit, she said yes and to sit down. Then Audrey explained that I had to write a letter to the GED gods and ask for an application to take the test. Then I would have to fill it out, mail it in, get it back, and see if I qualified.

I still remember feeling overwhelmed by the daunting nature of the GED endeavor (and my life) before me. Not just the mechanics of figuring out how to sign up to take the test, but also the fear of not being able to pass it. The mountain stretching before me, and on so many occasions in the future, looked so big and formidable that it seemed impossible.

But there has always been this way I do things despite the overwhelm. One foot in front of the other, one step at a time, borne of the sheer pressure of the fact that if I wanted to move forward in life, I had no other choice. Audrey said, in a detached, matter-of-fact way: "Write the letter to them asking for the application, and I will look at it."

So I went home and scratched out a letter asking for an application, took the bus back over to north Minneapolis the next day, sat down in the chair next to Audrey's grey metal desk, handed it to her, and sat in silence while she read it.

She read it, took off her glasses, and with a magical alchemy of calm, but serious disbelief, looked me right in the eyes and said:

"You can write well."

The moment was like a divine intervention. Perhaps I missed it, but I have no memory of anyone complimenting me on any aspect of me. The last 10 years of my life were spent paddling through the white water rapids of the relentless criticisms and judgments of others that had been internalized in ways I did not fully understand, and for the first time that I can recall, someone on the shores of my life threw out a mental life line for me to grab and hold onto.

Her words, "you can write well," started my journey to the shoreline of my life. I wish I could see Audrey in person, hug her, and thank her for the simple sentence that to this day fills my heart with such gratitude and that started my journey to believing in myself.

The power that we all have of creating such small "Lollipop Moments" for others (like Audrey gave to me that day) is beautifully illustrated in this short (6 minute) and sensational TED talk Leading with Lollipops by Drew Dudley. A must watch!