"You Were Essentially Unapproachable": A Lesson in Blind Spots.

In 2009, as the program director of general surgery, I used funds from my endowed chair to create a nascent leadership program for the surgical residents at the University of Minnesota.

My vision was based on my belief (dramatically strengthened by my work coaching surgeons) that surgical training programs should include leadership training in their curricula. The intense and appropriate focus on technical skills and patient care is essential, but one's ultimate success and fulfillment will depend profoundly on a solid foundation in personal development and the acquisition of crucial everyday leadership skills.

To keep things simple, I find the definition of leadership by W.C.H. Prentice from his classic (and still one of the most popular) article in Harvard Business Review entitled Understanding Leadership (attached below).

"Leadership is the accomplishment of a goal through the direction of human assistants. The person who successfully marshals their human collaborators to achieve particular ends is a leader. A great leader is one who can do so day after day, and year after year, in a wide variety of circumstances."

I use the phrase "Everyday Leadership" intentionally because I do not believe leadership is limited to those "in charge" or to work hours. We have all seen or lived under the yoke of a "leader" who is in charge, who is dreadful at the crucial human skills required to "marshal their human collaborators to achieve a particular task," except through the familiar command-and-control paradigm that is still flourishing in the surgical world.

But Everyday Leadership isn't just for work. It is for every interaction and every person you encounter, at home and at work. And the same principles and skills apply, no matter the context or situation.

It reminds me of the book It's Your Ship by Michael Abrashoff who, as a newly appointed captain (his first command of a ship) stood by the outgoing captain of the ship (a command and control Naval Academy grad like Abrashoff) and his family during the formal transfer of command ceremony and after, as the outgoing captain and his family were walking down the gangplank to leave, the entire crew of 310 sailors booed and jeered.

(I have been a member of a department of surgeons who all cheered in silence (or verbally in the hallways in conversation) upon the departure of a former chair of our department. Have you too, or do you wish someone would leave?)

The moment the captain was booed and jeered was a wakeup call that led Abrashoff to rethink his entire approach to leadership. He subsequently interviewed all 310 sailors personally, asking them about their goals, their lives, and what they wanted to accomplish in the Navy. He also asked each of them to come up with ideas for how they could do their job better. Many of the ideas were revelations to him.

Abrashoff then made a card for each sailor, wrote what he learned on each, stapled their picture to it, and memorized them all. In the process of doing the interviews, he notes:

"Something happened inside me as a result of those interviews. I came to respect my crew enormously. No longer were they nameless bodies at which I barked orders. I realized that they were just like me: They had hopes, dreams, loved ones, and they wanted to believe that what they were doing was important. And they wanted to be treated with respect.”

Abrashoff realized that the sailors had all been treated like cogs in a machine, a state of affairs alive and well in many departments of academic surgery and in the industrialization of medicine.

I would even boil down the concept of Everyday Leadership to what retired Navy SEAL Jocko Willink calls "getting people to care." By recognizing his own blindspots, Abrashoff stopped being a "command-and-control" threat and became a leader whom people felt safe enough to follow and care about.

To care about the mission, about you as the leader, about their team, and about the organization. It applies at work and at home.

Think about that for a minute, and reflect on when you have worked for or with someone who influenced you to care. When you care, you act because you care, not because some command and control person told you to act.

And the way to get people to care, to really care, is to see them for the unique human beings they are and to believe in their ability as human beings.

Abrashoff did it by vowing to himself to treat every encounter with every person on the ship as his most important job as a leader. He knew their names, their dreams, and their goals. He saw each crew member, and they could feel it.

The result of his new leadership approach?

Pre-Abrashoff, the Benfold was the worst-performing ship in the Pacific Fleet.

One year after Abrashoff became captain, the ship won the coveted Spokane Trophy, awarded to the best ship in the Pacific Fleet. But there's more:

- The Benfold operated on 75% of its budget for 1998, saving the Navy 25 million.

- The Benfold had the highest gunnery scores in the Pacific Fleet.

- Redeployment training time decreased from 52 to 19 days, giving all the sailors an additional 33 days of leave.

- He promoted 86 sailors in one year, twice the Navy's rate.

But the real proof: reenlistment skyrocketed from 28% to a staggering 95% in just one year.

Let that soak in. Based on one new captain who did everything in his power to see and believe in his crew, the sailors were willing to commit to four more years of their lives in the military.

The story of The Benfold and Abrashoff's success is fantastic, but there is another hidden lesson in Abrashoff's development as a leader: he had to figure out his blind spots. To quote Abrashoff:

"It's funny how often the problem is you. Whenever I could not get the results I wanted, I swallowed my temper and turned inward to see if I was part of the problem. I discovered that 90 percent of the time, I was at least as much a part of the problem as my people were."

In other words, he had to lead himself, and his crew. He took the time and made the effort to get to really know and learn about each member of his crew. But he also took the time to learn and understand himself and where his blind spots were; if left unrecognized, they could lead to unintended leadership accidents and failures that could have been prevented.

The concept of blind spots was completely unfamiliar to me in 2009 when I was the program director and had the 360 assessment. And it turns out - drum roll for the understatement - I was blind to my blindspots.

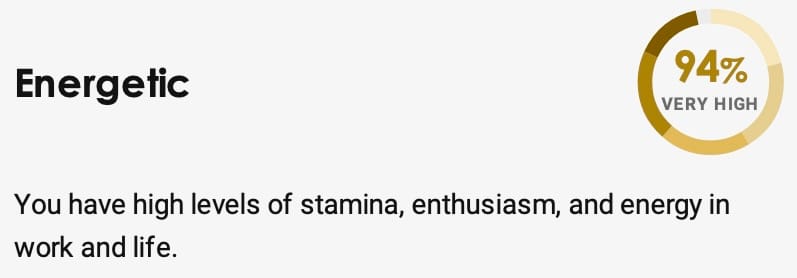

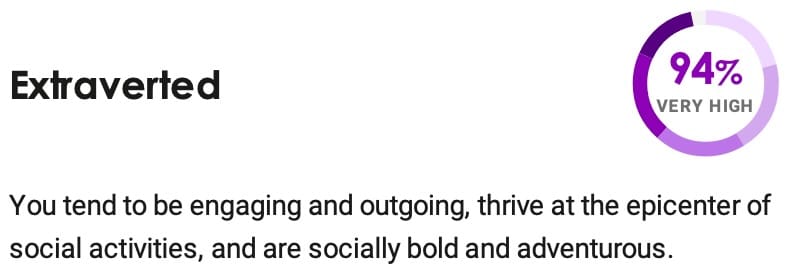

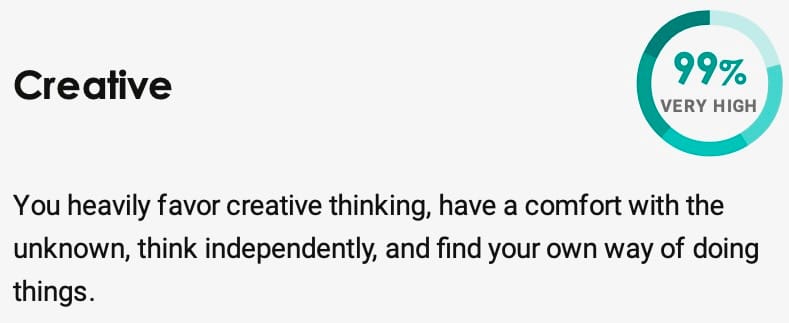

Let me explain. Most of us humans have aspects of our personality that are particularly strong. Here are a few of my traits from my PrinciplesYou personality assessment:

These traits are measured as percentiles relative to a population. So, in the energy continuum from low to high, I am more energetic than 94% of the population. Similarly, I am more extroverted than 94% of the population.

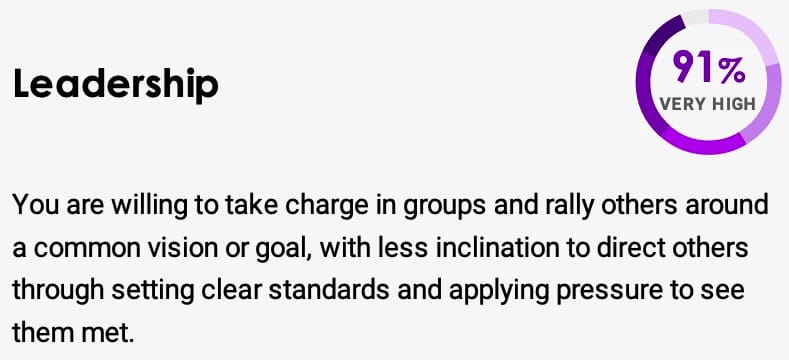

In the leadership trait, I am more willing to take charge and rally others around a common vision or goal than 91% of the population.

The high percentiles on these traits mean I am way out on the curve; these traits are powerful directors running my mental show.

Conversely, if my extraversion percentile were 8%, at the opposite end of the spectrum, introversion would be one of the main directors of my mental show.

Or if my extraversion percentile were 50%, neither introversion nor extroversion would be strong, and I would be more balanced. It would be easier for me to be versatile and flexible in either direction, as needed by the circumstances.

People at the high or low end of the distribution have much more difficulty flexing in the opposite direction because the trait is so strong. The vast majority of us have some traits in the high percentile range, and since these traits are like default neural pathways—they are the easiest for your brain to fire - flexing to the other end of the trait percentile takes such deliberate effort.

If we add my percentiles in these three traits up:

Extraversion (94%) + Creative (99%) + (Leadership (91%) + Energy (94%) = "You are a force to be reckoned with."

That comment is from a friend and surgical colleague. I remember the moment he said it. It was sort of a compliment, and sort of not a compliment. At the time, I (of course) took it as a grand compliment. My chest puffed up a bit in my little private mental wine cellar when he popped the cork on his bottled up perception of me.

The concept of blind spots was completely unfamiliar to me in 2009, when I was the program director and had my first 360 assessment. It turns out—drum roll for the understatement of the decade—I was blind to my blindspots.

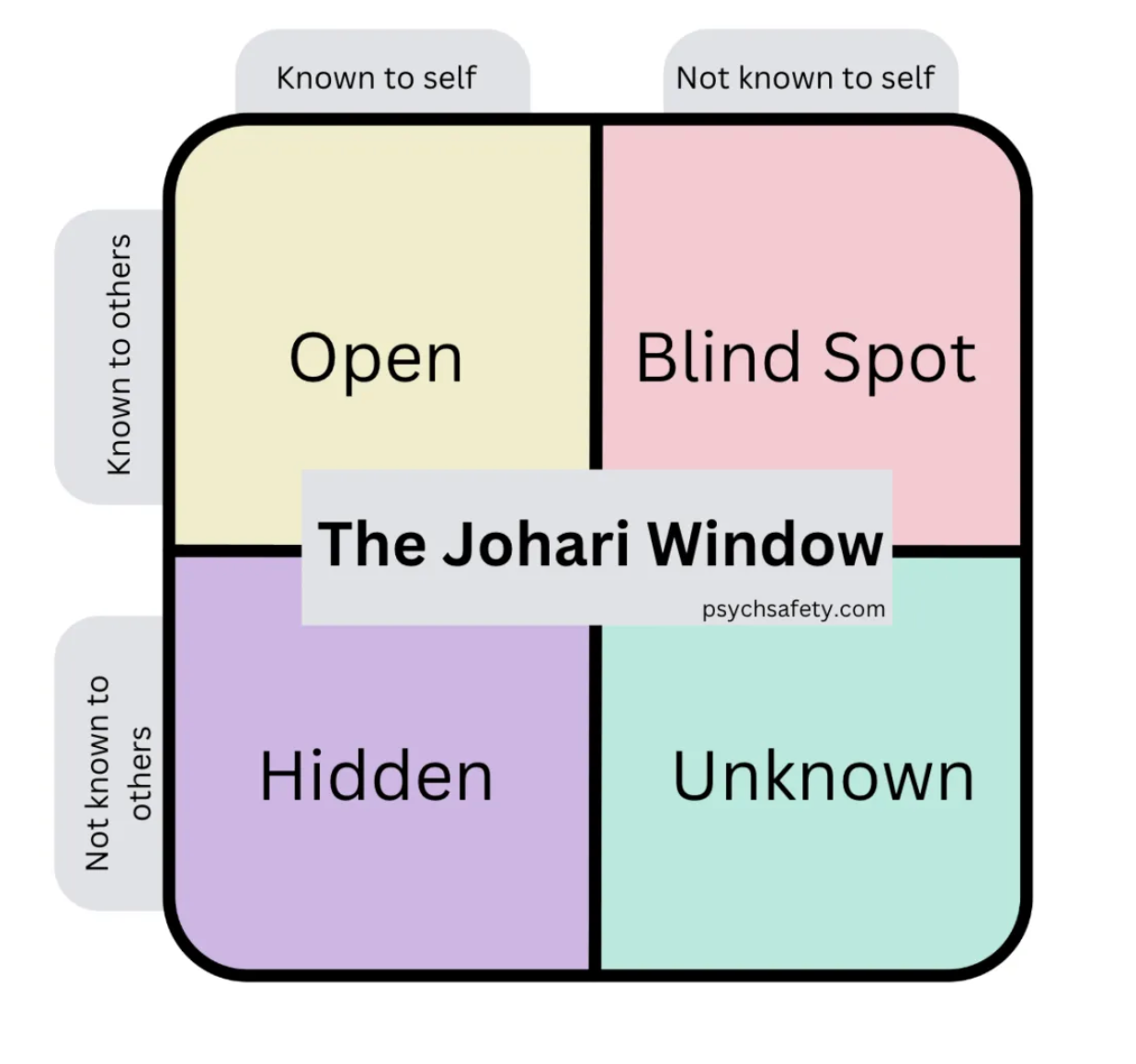

In psychology, there is a classic tool called the Johari Window that explains exactly why this happens. It divides our self-awareness into four quadrants:

My 360 assessment was a high-resolution look into that blind spot quadrant. For example, my Principles You profile shows I am in the 94th percentile for Energy and the 99th for Creativity. To me, these were just facts of my existence. It felt like "normal" to me. But because these traits are so far out on the curve, they are "powerful directors" that run the mental show, and they impact everything.

Therein is the challenge. If I were a monk living in a cave, my high or low percentiles wouldn't really matter. I only have to deal with myself. No one else has to deal with me.

But when you are out in the world, interacting with others, these strengths can become a liability when overused in our Everyday Leadership.

(One important point about the personality assessment. I took the assessment 2 years ago. The 360 assessment is from 17 years ago. My current strong traits were present in full force back then.)

The difference between now and then? I am aware of my blind spots, and I can flex my approach depending on the context. I have become more versatile.

Another story to help illuminate: The Superpower Trap: Fastballs and Force.

Sandy Koufax is one of the greatest pitchers of all time. He was brilliant but had struggles and retired briefly, only to become bored. He decided to go back for another try to see just how good he could become.

Koufax's superpower was his fastball, and he threw it hard and often. Mickey Mantle noted the following after being struck out by one of his fastballs: “How are you supposed to hit that shit?”

No wonder he loved to use his fastball so much. It was his superpower.

After his return, had a shot to show his mettle in a B-Squad game against the Minnesota Twins. Before the game, his catcher, Norm Sherry, told him, "If you get behind the hitters, don't try to throw so hard" because of his tendency to lose his temper and throw hard and wildly whenever he got into trouble.

During the game, Koufax followed Sherry's advice but soon reverted to his superpower - his rocket fastball - and ended up walking 3 in a row. Now the bases were loaded with no outs in the fifth inning.

Sherry stepped out to the mound and reminded him to stop throwing so hard. Koufax listened, modified his pitching to the context of each batter and the circumstances, and ended up striking out the other side and finished the game with 7 no-hit innings.

Koufax went on to become one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history.

Not because of his superpower - his fastball. Because he trained himself to become a versatile pitcher who could flex his pitches to meet the demands and context of the situation.

There is a parallel for surgeons here who, understandably, veer towards command-and-control as their fastball, since it works in the OR and in crises, but can create unintended leadership accidents.

Again, take my superpowers:

- Energy (94%) can look like Chaos to a team that needs a calm, steady hand.

- Extraversion (98%) can look like Suffocation to a colleague who needs space to think, reflect, and provide a critical insight.

- Creativity (99%) can look like Unpredictability to an OR staff that relies on the "protocol" to keep patients safe.

The difference between me now and me in 2009? As you can see from my recent personality profile, my superpower traits are alive and well. What has changed is my ability to adapt my approach to the environment and context. I have become a more versatile Everyday Leader.

Flexibility, versatility, and adaptability are the hallmarks of resilience in any system. Everyday Leadership is the ability to walk into a room, read the context, and decide which "pitch" (back to Koufax again) the situation actually requires. Sometimes the team needs your energy. Other times, they just need you to stop throwing so hard so they can do their jobs. Or sometimes they need you to be the catcher that comes up to the mound as a coach to help you get your shit together.

My awareness of my blind spots and my efforts to learn how to flex have literally transformed my relationships. Here are two of my children's comments about me, before I worked on them, and after I worked on them. To solicit their feedback, I texted them the following question:

"Would you be willing to write a few sentences about how I’ve changed, if at all, from your perspective? I am NOT fishing for compliments - if you can’t think of anything, no problem! No pressure❤️"

My son Mike wrote:

Pre-blind-spot awareness: "You were essentially unapproachable."

Post blind spots awareness: You’re one of the more caring, reliable, and emotionally intelligent people I know. You’re there to help with any problem, and the old “better keep that to myself” thinking with you in the past is gone. The intrinsic qualities that make you great - caring, disciplined, curious, and your drive for perfection did not change, but your interest in others and understanding of people and different perspectives were transformed. To this day, I cannot believe some of what comes out of your mouth and mind - in the very best way.

As a leader in any capacity, do you really want someone (especially your children) to feel they "better keep that to myself?" It's called lack of psychological safety.

My daughter Rachel wrote:

Pre-blind-spot awareness: You were rigid, unapproachable, and closed-minded, you lacked empathy and had a narrow definition of how life should be lived, and perfection was the only option.

Post-blind-spot awareness: now you’re open and approachable, and vulnerability is a good thing. You listen without judgment and offer grounded advice not rooted in preconceived notions of what people should do…you truly listen to the situation and remain diplomatic, considerate, compassionate, and you acknowledge that everyone has faults and those faults can be a good thing.

In closing, consider pondering this:

If a Navy Captain can transform 310 cynical sailors in an entrenched hierarchical command and control environment into the best crew in the Pacific Fleet by seeing them as the unique human beings they are and believing in their potential, can you imagine what you could do with your surgical team, colleagues, or family?

Below is a video I had NotebookLLM create from my uploaded written comments from my 360 assessment that is spot on. The written comments were from these two sections of the report:

- What are this person's most significant strengths and why?

- What are this person's most significant areas for development and why?

The video (I think) does a great job of highlighting the interplay between my strengths and the blind spots they created.

Are You Ready to See What’s Behind You?

You don’t have to do this "detective work" alone. Every elite pitcher needs a catcher who can see the whole field and tell them when to take some heat off the ball. My coaching is designed specifically for high-achievers ready to:

- Audit the Blind Spots by using precise tools like Principles You and comprehensive 360-degree assessments (verbal or written) to reveal the "Powerful Directors" of your mental show.

- Develop Your "Pitching" Versatility by learning the specific skills required to become a versatile everyday leader, capable of adapting your approach to any environment or context.

- Transform Your Relationships by deploying new "pitches," which will allow to embrace the principles of really seeing and believing in others—especially your loved ones.